DIAGNOSIS AND DESCRIPTION

Our initial NICU consultation offered us little hope. And the somber, blank expression on the nurse’s face while delivering our news, has been burned into my memory. With her words, our son’s birthday became the best and worst day of my life all in one.

Leaving the NICU, I didn’t think our son would survive, and I couldn’t wrap my mind around it. How could a baby who looked so perfect and healthy be so broken on the inside?

I was empty and incomplete. I just wanted to hold him, and our separation paired with the distance to the maternity ward, was unbearable.

When we finally reached my room, we were greeted by an unfamiliar nurse expecting two people in a celebratory mood. Smiling ear to ear she greeted us, “Hi! Congratulations! How are you feeling, Momma?” “Not good,” was all that I could get out.

I had been living in the hospital for 6 weeks, but in another ward. Here, strange nurses were asking me questions about myself that I wished they already knew. I wondered why, after all this time (and in a time like this) am I being asked questions about myself?

The new and unknown nurses teamed up to transfer me from my OR bed to my new bed. I can’t lie, it really freaking hurt. All feeling had returned to my post-op body. Everything was setting in. And just then, nurse Peggy walked in. I burst into tears.

Nurse Peggy was one of my antepartum nurses and more. In addition to providing care for the previous six weeks, she had become a sort of maternal nurturer to me. And to no surprise, here she was, hugging me like a daughter, while letting me sob into her shoulder.

Patient with me while I tried to stop crying, she was still in the room when the surgeon arrived. I told her she didn’t have to stay. Of course, she didn’t listen.

Now, it is no exaggeration to say our whole life changed when the surgeon began speaking.

Smiling and confident, he said the words we were least expecting. Our son’s condition was treatable with surgery. And more, he assured us our son’s life-saving operation had a near 100% survival rate.

Looking at each other in disbelief, my husband and I tried to make sense of his words. The surgeon continued, “Surgery needs to happen soon. These babies can only get nutrition through an IV and it doesn’t keep them satisfied for long.” Our son’s operation was scheduled for the following morning.

We were warned our son would be on a respirator following surgery, and would need additional exams to determine whether or not he had further, associated complications.

In turn, we asked him questions about our son’s future that he couldn’t answer with certainty. But, at last, we had reason to believe that our baby could survive. And to top it off, we were given permission to return to the NICU. We were finally going to be with our son.

It took months, maybe years, for the fear and shock of our son’s diagnosis to wear off of my husband and I. We’ll be grateful everyday for the rest of our lives, but we still don’t understand why we were given zero hope that morning in the NICU.

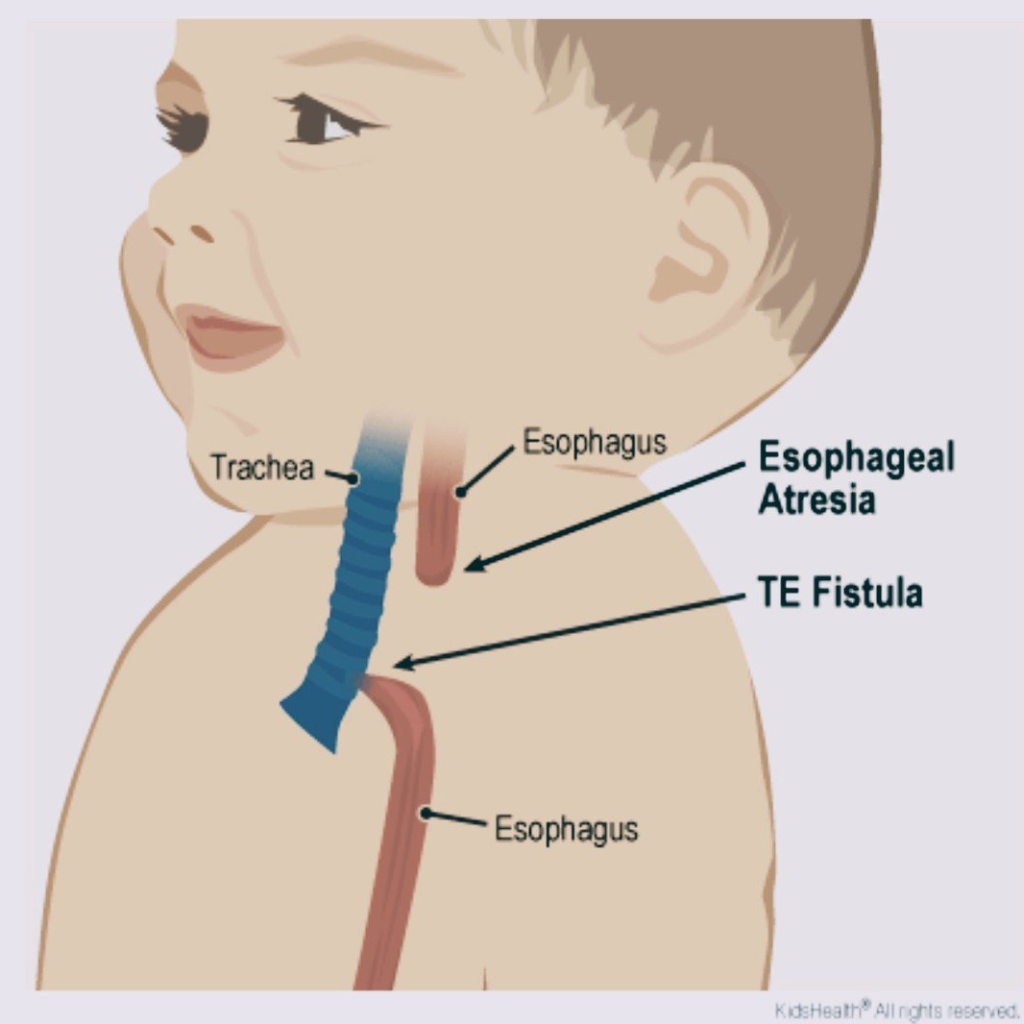

TE fistula with esophageal atresia image curtesy of Akron Children’s Hospital

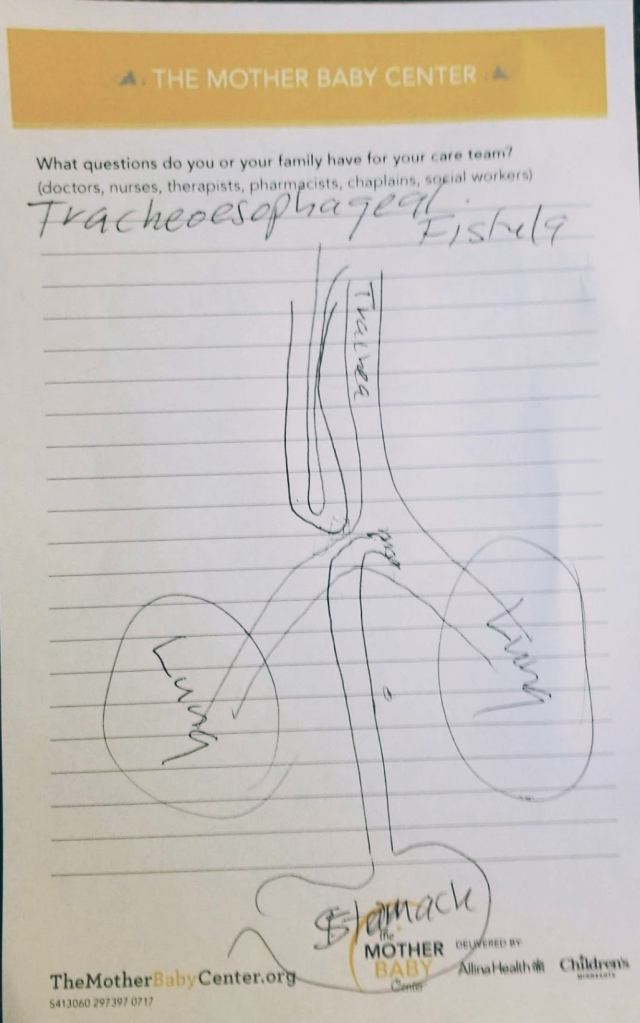

Surgeon’s drawing of our son’s TE Fistula with esophageal atresia

So what is tracheoesophageal fistula? Here are some quick facts, with links to the supporting medical websites below:

- Tracheoesophageal fistula is a birth defect where the esophagus and trachea (airway) have an abnormal connection

- TE fistula often occurs with esophageal atresia. Meaning the esophagus grew in two parts. One part connected to the mouth, the other part connected to the stomach (see below image)

- The only way for these babies to eat and drink on their own is with corrective surgery. The surgery needs to create a full and secure connection between the mouth and stomach via the esophagus, and between the airway and lungs via the trachea

- TE fistula occurs in approximately 1 in 5,000 babies

- Up to one half of babies with TE fistula also have another serious birth defect including heart, digestive tract, kidney, and muscular/skeletal problems. X-rays and further testing would be necessary

- TEF was a “hopeless congenital anomaly” not long ago. The first successful repair surgery was not until 1941. With survival rates nearing 100% only in the last few decades

For TEF SERIES PART 1: PREGNANCY AND DISCOVERY, visit:

https://believableshe.com/2021/06/03/series-tracheoesophageal-fistula-from-nicu-to-two/

REFERENCES

https://www.akronchildrens.org/kidshealth/en/parents/te-fistula-ea-html.html